Your Argument Sucks is a recurring column where I tackle major arguments about the modern US political system by detailing actual facts through the narrative of historical context. All I ask is this: Go into these posts with an open mind and the ability to change said mind, if necessary, no matter which side of the argument you fall. I did. And because no matter how much you want to be right, no matter how much being wrong would flip your world upside down, being able to accept the facts and alter your opinion as necessary is a vital part of co-existing. And maybe, just maybe, your argument will no longer suck.

The Arguments

- “America is a Christian nation!”

- “Our country was founded under God.”

- “The Founding Fathers were not Christians.”

- “God is in our Constitution/Pledge and needs to stay there!”

- “‘Under God’ in the Pledge is Unconstitutional.”

- “God needs to be put back in our schools!”

- “The Separation of Church and State is being ignored.”

The Complex Explanation

As discussed in the previous post, one of the biggest differences between the modern Democrats and Republicans comes down to social politics. Democrats are socially liberal, and Republicans are socially conservative. Again, this means Democrats want the government to stay away from controlling personal issues—such as anything to do with one’s sexuality, civil liberties, women’s rights, abortions—and Republicans want the government to have a firmer hand in all of that. The most common reason Republicans use? Religion. Liberals, to many modern social conservatives, are an affront to God. And not just any god—the Christian God.

Religion is and has always been a controversial issue in the United States, from the pilgrims to the Constitution to now. There’s no denying that religion was a key influence in the formation and history of the United States—but that is a different argument than if the US is a Christian nation, as well as any major argument given on the topic of religion in the US currently. It would be similar to saying a balloon is a helium-created toy. It isn’t. Helium can be used to make a balloon float, but it is and was a balloon before helium was added to it. It isn’t made from helium—it’s made from materials like rubber. Some people, however, feel that helium makes the balloon the best, while others say it can be filled with carbon dioxide, water, or nothing at all and still be fun.

The US has always touted itself to be, historically, the country of religious tolerance and freedom. Schools teach kids about the pilgrims coming from England to escape the religious persecution so they can freely worship how they wanted. The puritans were soon to follow for the same reason. The Founding Fathers were all deeply religious men who based the Constitution on God-given rights, including the freedom to worship in whatever religion you please without persecution. We are a Christian nation, under God, who blesses America, dinners, and sports events—but under the law of a separation of church and state in order to avoid the religious tyranny that brought everyone here to begin with. But how true is any of that?

Let’s start at the beginning.

Who even discovered America? It’s not overtly important to this topic, but it is a mild fact that is often misunderstood in the United States. First and foremost, the obvious answer here is the natives. Any Native Americans who were here before anyone else are the ones that discovered it. That’s why they’re called natives. But that’s not what anyone means with this question. What outsider discovered it first? Technically, as far as we know, that honor goes to Norse Viking Leif Eriksson around 1000 A.D. He landed in what is modern day Canada. And to stay on topic, he was a converted Christian. But his journey, arrival, or stay had nothing to do with his religion.

In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue… and found the Bahamas. While he did not discover America, he found that there was more land that the rest of the world was unaware of (but still swore up and down he found the Indies). Also, rumor has it, he was Jewish. Anyway, a bunch of other people then explored the area during what is called the Age of Discovery, though the most important one in our founding history was an Italian (and Christian, though, again, irrelevant) explorer named Amerigo Vespucci, who made multiple trips—controversially one that may have taken place prior to Columbus that landed him in the Bahamas and Central America. Another, and more important, trip landed him in South America, where he was the first person to recognize that it was a completely separate continent than Asia—thus getting the whole thing named after him.

Next up is the pilgrims, right? Nope. Some French Protestants (Calvinists) called Huguenots set up in what is modern Florida, though that didn’t last long—they were wiped out by Spanish settlers within a year. They also later, and more famously, set up in the Dutch colony, New Amsterdam (modern day New York City). After that were many failed European settlements, including England’s mysterious lost colony, Roanoke. Finally, there was the first successful colony, Jamestown.

In 1620, the pilgrims landed in the New World to escape the religious persecution happening back in England. They were similar to the puritans that arrived shortly after, with one primary difference: The puritans continued religious persecution, running what was essentially a theocracy that did not tolerate other religions by threat of banishment or death. Catholics were also one of the most commonly persecuted denominations—remember, it was a big deal when John F. Kennedy became the first Catholic President. But why Catholics? Because the Church of England, the one persecuting other religions (such as Protestantism), was Catholic. You could say it left a bad taste in people’s mouths. It’s also a primary factor in why the Irish were frequently discriminated against.

What does this have to do with the Founding Fathers and the Constitution? For the sake of these arguments, not a lot. But it leads itself thematically to the fact that the land that became America has always been a land of violent religious persecution.

So let’s move on to what you’re really waiting for: Were the Founding Fathers Christian, and did they build this country as a Christian nation? As you might have expected, it’s tricky. The short answer is the majority were some form of Christian—but it isn’t that easy, partly because they tried to keep their religious beliefs out of their public lives, and partly because then, like today, people can qualify as “Christian” while not quite being Christian. To make this easier (since there were over 50 of them), we will look at the biggest and most important figures.

The slightly longer short answer is this: some were straight-up Christian (Samuel Adams), some followed Enlightenment-inspired Deism (Thomas Paine), and some were a kind of mix (George Washington, Ben Franklin). And then there was Thomas Jefferson. But before we can get to Jefferson, we really need to understand Deism and how it affected these men. Deism in its purist form is this: I believe in God. That’s it. There is no biblical belief or spirituality. They followed their own ability to reason with a common-sense moral code. It’s similar in concept to modern-day atheists, but they still believe in a higher power. Thomas Paine was the biggest name in this purest form of Deism. The Enlightenment and Deism is also the source of the separation of church and state, which we will return to later. The majority of our big names, like Washington and Franklin, were Deists with an *. In other words, they believed in God and Jesus, minus all the biblical “supernatural” stuff. There is no Divine Intervention. There were no miracles. No burning bush. Nothing. God and Jesus exist; they act as the moral standard; they stay out of our business.

Now, Thomas Jefferson—arguably one of the most important Founding Fathers, and the man responsible for the separation of church and state in the US—was far closer to Deism than pure Christianity. Jefferson believed religious teachings, like the Bible, were altered by man for personal or political gain. He also subscribed to a version of Unitarianism—a religion that basically merges all the major religions. They believe in one God rather than a Trinity, and Jesus was a savior and moral teacher of God but is not God Himself. The point is to focus on the general moral standards of religion rather than the specific laws and rulings. In fact, Jefferson more or less rewrote the New Testament to remove Jesus’ miracles in order to focus purely on just that. This was called The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, also commonly known as the Jefferson Bible.

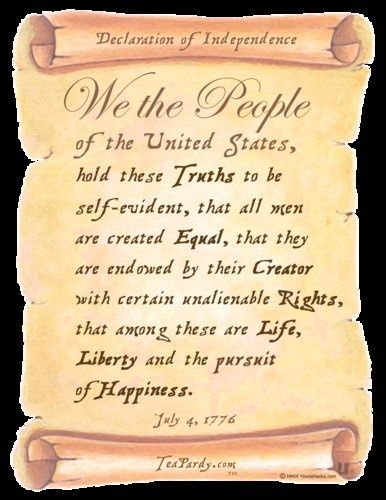

One of the primary mentions of God in founding political documents was the following line from the Declaration of Independence:

There are other mentions of God in the Declaration, as well. Clearly, here, they are talking about their God-given rights, right? Superficially, yes. But within context of the time, maybe not so much. These people had just split from an overly controlling monarchy, a monarchy of humans that gave or took away the rights of its people. The Declaration was showing that these people are now independent from the control of man. While still religious in nature, the wording is specifically vague to include more than simply Christianity.

Not all of the men who were involved with the Declaration were involved with the Constitution, either. However, their views on religion did, in fact, form it—but not in the way many think. Religion was, by and large, left out of the Constitution. Due to past persecutions thanks to religious rule, the majority of the Founding Fathers wanted to make sure to exclude religion and God from its writing. It was purposefully written as religiously neutral, not wanting religion to inform or control any aspect of the governing document. In other words, they didn’t want to repeat history with what happened back in England.

They also claimed no state or national religion (and, to this day, there is still no official religion). The Constitution states “no religious Test shall ever be required as a qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States,” meaning nobody can be required to be a certain religion to hold public office. And in 1791, the First Amendment was added, which included a freedom of religion, and that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” In short, the government is not allowed to favor any religion or ban or discriminate against any religion. Due to this, there must be a “separation of church and state.” While those words are never mentioned in the Constitution itself (they were said by Thomas Jefferson), it is inherent in the disallowing of favor in any given religion. The only way around it would be to include, equally, every religion and no religion—an impossibility. Therefore, a separation of church and state, while not directly mentioned, is not only implied but required.

However, it was only on a federal level. The enforcement was extended to the states in the 14th Amendment, which doesn’t mention religion specifically, but includes, “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” This basically says “You know all these Constitutional laws that are enforced on the federal government? All you state governments have to follow them, too.” States fought this for years, but a 1925 Supreme Court ruling laid out that, due to the 14th Amendment, the states must abide by the separation of church and state as written in the First Amendment.

This is not to say that states 100% always abided by these Constitutional laws.

Religion has been a source of contention regarding the Constitution since the Constitution was implemented. The Supreme Court was controversial when a Justice declared the US to be a Christian nation in 1892, a written statement that had to be clarified as opinion. Many amendments to add specific references to Christianity into the Constitution were attempted over the years. The NRA (the Reform one, not the Rifle one) attempted to put through a Christian amendment that stated we, the people, are “acknowledging Almighty God as the source of all authority and power in civil government, the Lord Jesus Christ as the Ruler among the nations, His revealed will as the supreme law of the land, in order to constitute a Christian government.” Of course, this has never gone through.

One of the longest-lasting controversies toward attempted breaches in the church—state relationship is one that got through. In 1892, a Christian minister (and socialist) named Francis Bellamy wrote the Pledge of Allegiance and published it in a children’s magazine called The Youth’s Companion. It originally read as follows:

“I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

After this time, it became popular, and in 1942, President FDR signed a law about flag care, including the Pledge. The Pledge was slightly altered over the years until its biggest and most controversial change. In 1954, during the height of the communist Red Scare, President Eisenhower added “under God” as a counter to the “godless commies,” and it’s been under fire ever since. Jehovah’s Witnesses first complained, since kids had to say it in school. The courts actually ruled that the teachers could force them to say it despite being against their religion, until about 3 years later, when it was decided they broke the First Amendment. “Under God,” however, remains in the Pledge, despite many noting its Unconstitutional adherence.

Similar to the Pledge-in-schools controversy, a common argument is the downfall of America’s moral code since mandatory prayer was removed from public schools, seemingly by atheist or Godless culture. But this also did not begin as a modern issue. For well over a century, public schools would commonly begin the day reading or praying from the King James Protestant Bible. Many proponents of this were anti-Catholic Protestants hoping to shift Catholic children away from Catholicism. This issue blew up in the latter half of the 19th Century when Catholics protested. They voiced their concerns and fought against what they felt to be an Unconstitutional sleight against them. Irish Catholic women became teachers, and many other religions began setting up private and parochial schools, not funded by the government.

By the mid-20th Century, twelve states had made it legally required to read from the Bible at public school. In 1955, the New York Board of Regents reacted to the communist Red Scare by writing and recommending (though not requiring) a prayer to be said during school. A Jewish man, Steven Engel, noticed his son having to pray differently than his religion taught and fought back. The claim was this Regent’s prayer established a Christian religion via a government body, violating the First and Fourteenth Amendments. After years of fighting it, Engel won his case in 1962. The Engel v. Vitale Supreme Court ruling declared the Regent’s prayer unlawful in public schools.

The following year, Supreme Court case Abington School District v. Schempp furthered the ruling. In 1956, Ellery Schempp was a student in the Abington Township of Pennsylvania. His school required that each student read 10 Bible passages every morning. In protest, Schempp brought a copy of the Qur’an to read from (though he was not Islamic—he was Unitarian Universalist, similar to John Quincy Adams and Thomas Jefferson), for which he got in trouble—not because he was specifically reading the Qur’an, but because he was not reading from a Christian Bible. Eventually, this expanded into the Supreme Court case that, in 1963, upheld the Engel v. Vitale ruling, making prayer in public schools unlawful.

Abington School District v. Schempp wasn’t the only case in 1963. There was another, more famous inclusion that was consolidated with Schempp’s Supreme Court case: Murray v. Curlett. A highly controversial, vocal atheist, and activist woman named Madalyn Murray O’Hair fought prayer in public schools on similar grounds to Schempp, as well as other separation of church and state cases. After the ruling, O’Hair moved to Austin, Texas, and established the American Atheists, a movement that, among other things, was created to uphold the separation of church and state. She quickly became the face of the removal of prayer from schools, even so far as to receive death threats.

In 1995, a Catholic parent and a Mormon parent in Texas sued their school district for public prayer at the school football games. This case, Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe, concluded that school-sponsored events such as sporting events cannot openly request specific religious prayer, as it establishes a religious bias against the First Amendment.

While schools and school-based events are not allowed to make prayer or Bible reading mandatory, these rulings do not ban religion as a whole. Students are still allowed to silently pray at school throughout the day or at sporting events to themselves. They may participate in religious clubs or activities before or after school. They can bring and silently read from any religious text they wish. Religious information can be found in school libraries. Religion can be discussed within historical contexts in lessons.

And despite all of these rulings, the First (and, by proxy, Fourteenth) Amendment remains one of the most challenged Amendments (along with the Second, which we will get to in a later discussion) in the United States. Even to this day. Another, more modern religion-based First Amendment violation was in 2017, when President Donald Trump attempted “Muslim Travel Bans,” a discriminatory law against travel from specific Muslim countries into the US. This law was disallowed due to its stringent breaking of the First Amendment, making it Unconstitutional.

In short, religion has always been involved with and an issue for America. Violence, discrimination, persecution, division, and control has come from a need to have the United States, ruled by a secular Constitution which was spawned from and rightfully demands religious freedom and governmental unattachment to religion, as a specifically Christian nation, becoming exactly what the pilgrims were trying to escape and the Founding Fathers were trying to avoid.

TL;DR

- While religion played a major role in the history of the United States, the Constitution remains a wholly secular document, unattributed to any religion or religion in general.

- The Pledge, as it cites ‘under God,’ is Unconstitutional.

- The Founding Fathers were religious in that most believed in a God, but not in the typical biblical, Christian sense—more in a moral teachings sense, minus the “supernatural” stuff. They did not intend the United States to be a Christian nation or show favor to any religion at all.

- Mandatory prayer, preference, or religious practice in public school is Unconstitutional. And it has been fought to be removed primarily by the religious, not atheists.

- The separation of church and state is being blatantly ignored, though it always has been since its original inception in the 18th century.

Christianity is bullshit. They come into other places trying to get people that their way is the right path and then make them do this and say “if you don’t read the Bible, you don’t get any food”.

LikeLike

I was raised Catholic, went to private school for 9 years, went to church twice a week for at least a decade, etc. My whole mom’s side of the family is pretty religious. I fell out of it all around my teen years and haven’t unforcably been to church since I was 18. But I have continued to study religion in general and know quite a bit. I’m not atheist, but I am anti-how people utilize religion. But yes, historically, Christians have been some of the worst people in the world. But I think Americanism is even worse, because it’s politics under the guise of religion, when it’s really just selfishness and propaganda most of the time, and tied to Capitalism. America is that moment in the Bible where Jesus gets mad at the tax collectors and starts flipping tables. Except they think they’re Jesus when they’re really the tax collectors inside the church.

LikeLike

I grew up in a fundamentalist household, and was surprised when I first discovered that the U.S. founders were not a group of devoted Christians trying to establish a Christian nation. The idea that the U.S. is inherently a Christian nation is a big part of the Christian-American mythos—so much so that the idea is taken as obvious by most Christians. Now that I know better, the idea of a Christian nation built on the concept of freedom of religion is an oxymoron; luckily for Christianity (and most religions), critical thinking is not viewed as a critical necessity.

Very enjoyable read. I’m trying to get better acquainted with U.S. history, I and definitely learned a few things from this article!

LikeLike

Thanks for reading! Yeah, writing this project has opened my eyes to a lot of things and strengthened my knowledge and passion for history and how so many people have so many things inherently wrong.

LikeLike